Flash Game Dev Tip #1 – Creating a cross-game communications structure

Tip #1 – Flixel – Creating a cross-game communications structure

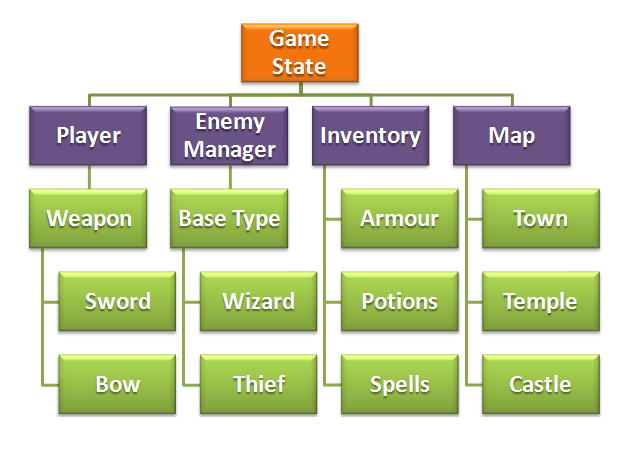

As moderator of the flixel forums there is one question I see time and time again. It starts something like this: “how can I make X talk to Y, especially when the State changes?”. The problem is a classic OOP one, and thankfully there is a classic OOP approach to solving it. Have a look at the following diagram:

Here we have part of a mock-up Game State structure for an RPG game. As part of the state you can see the Player, an Enemy Manager, an Inventory (which both Player and Enemy can share) and a Map consisting of several important locations.

Of course this is just a rough-example, so don’t get bogged down in the semantics or structure of it. Instead think about how inter-dependant all of these objects are on each other.

- For example perhaps the Temple won’t allow the Player to enter if he is carrying a weapon.

- What if when fighting the Thief you win, but he steals a Potion from your Inventory before running away.

- Perhaps the enemy wouldn’t even attack you if he realised what Sword you were carrying?

- A Wizard casts a fireball at you. How much of the damage does your Armour repel?

In all but the most simple of games it’s vital that your game objects can communicate with each other. And communicate effectively.

When you create your Game State you could first make the Player object, and then pass a reference of that into say the Enemy Manager, so the baddies it creates can check out your vital stats prior to attack. But passing references around like this gets messy, and it’s all too easy to leave “open ends” that don’t get cleared up as needed. In a worse-case scenario they could leak memory and crash Flash Player. And in a “best case” they just confuse you during development.

One Ring to Rule Them All

My suggestion is to use a Registry. A Registry is “A well-known object that other objects can use to find common objects and services.” (Martin Fowler, P of EAA) – sounds ideal, right?

They are extremely easy to create too. In your Project create a file called Registry.as – Here is an example file based on the structure above:

package

{

import flash.display.Stage;

import org.flixel.*;

public class Registry

{

public static var stage:Stage;

public static var player:Player;

public static var enemies:EnemyManager;

public static var inventory:Inventory;

public static var map:Map;

public static var weapons:Weapons;

public static var potions:Potions;

public static var spells:Spells;

public static var previousLevel:int;

public static var enemiesKilledThisLevel:int;

public static var enemiesKilledThisGame:int;

public static var arrowsFiredThisGame:int;

public function Registry()

{

}

}

}

It consists of a bunch of static variables that map to the main objects required in our game. Not everything has to go in here, just the objects that you need to either retain their content when you change state, or objects that you know you’ll need to reference from elsewhere in your code, no matter how deep you get.

You can also see a few stats (previousLevel, etc) that are just holding details about the number of baddies killed in the whole time they played the game. Perhaps they can be used for achievements.

So how do you use them?

Quite simply by referencing them in your code. For example say we’ve got a Soldier. Our class file Soldier.as contains all the functions he can perform. One of them is attack, but before he attacks he checks out the player to see how much health he has. We do this via the Registry:

if (Registry.player.health < 50)

{

attack();

}

So our wimpy Soldier will only attack if he thinks he has a chance of defeating you! "health" is just an integer in our Player.as file that holds the current health of the player. You use the Registry as a conduit between the objects in your game. It's a means for any object to gain access to another object or service, regardless of its depth in your structure. Once you start planning and thinking in this way, designing your game starts to become a lot easier. Your game objects can "share" knowledge of the game without the need for passing references or instances. Another example. Here we have a CharacterDialogue class. It's responsible for the speech and interactions between characters in the game. It too has access to the Registry, which means you can do things like:

if (Registry.map.castle.getNumberOfSoldiers() >= 20 && Registry.player.potions.hasStealth == false)

{

speech = "The castle is heavily guarded. A stealth potion should help";

}

On a more “arcade” level enemies can use the Registry to get player x/y coordinates, or to find out if he’s colliding with something. I often have a class called SpecialFX in my games, which is referenced in my Registry as fx. The class contains various particle effects such as “spurting blood” and “sparks”. This means that when an enemy dies, in their kill() function I can call:

Registry.fx.bloodSpurt(this.x, this.y);

As long as the “bloodSpurt” function is public then a shower of blood will erupt forth, based on the x/y location of the enemy that just died.

I prefer this approach to the opposite. Which would be that the enemy creates a “blood spurt” particle when it dies and is responsible for displaying and running that. I just find the above neater. It ensures that the classes deal with their specific tasks and don’t “cross breed”.

Populating your Registry

If you use the example Registry above then it’s just full of empty (null) objects. You need to instantiate each object before it can be used.

When you do this is up to what fits best for your game, and it will vary from game to game. But there are two common methods:

1) When the game first starts (after the pre-loader has completed)

2) Every time your main Game State begins

If you do not need to maintain objects once your game has ended (i.e. the player has died and was sent back to the main menu) then you can populate your objects right as the first thing you do when your GameState starts:

public function GameState()

{

super();

Registry.gui = new GUI;

Registry.player = new Player;

Registry.map = new Map(level1);

Registry.inventory = new Inventory;

add(map);

add(player);

add(gui);

}

Here is the constructor of my GameState.as file. We create the objects and then add them onto the display list.

If you don’t want to “over-write” the player like this (perhaps it has stats you wish to retain no matter how many times the game is re-started) then you’d need to move the object creation elsewhere in your game. Perhaps as part of your FlxGame class. Here’s an example:

package

{

import org.flixel.*;

public class GameEngine extends FlxGame

{

public function GameEngine()

{

Registry.player = new Player;

Registry.reachedLevel = 0;

super(640, 480, MainMenuState, 1);

}

}

}

It’s up to you where you do this, just don’t forget to do it!

House-Keeping

If you have objects in your Registry that you don’t need to keep should the game end, then you can create an erase function inside your Registry. All it needs to do is set the objects to null:

public static function erase():void

{

player = null;

hud = null;

debris = null;

weapons = null;

map = null;

aliens = null;

pickups = null;

sentryguns = null;

storyblocks = null;

lazers = null;

hacking = null;

boss = null;

bossfire = null;

enemyfire = null;

terminals = null;

}

And then just call Registry.erase() when your game ends, before it changes to your menu state.

This will ensure you keep memory down. As flixel doesn’t let you create any custom events, then you shouldn’t have anything left lingering by using this method.

Final check-list

1) Registry.as should be at the top level of your Project

2) All vars declared within it should be public static if you want to access them outside of the Registry class itself

3) Access it from anywhere by calling Registry.object – Do not create an instance of it.

4) If you use FlashDevelop then you will get full auto-complete of anything you put into the Registry!

5) You can put Flixel base types in there too: spaceShip:FlxSprite is perfectly valid.

6) If needs be you can also put common functions in there. But try to avoid this practise, there are better ways.

Further Reading

You can read about the Registry pattern in the book Patterns of Enterprise Application Architecture by Martin Fowler.

You could extend the Registry to be a singleton, so that only one instance of it may ever exist (and further attempts to create them would error). There are pro’s and con’s for doing this. Personally I don’t need to as I never instantiate my Registry anyway, but I can see the merits of adding that “safety net” check in.

Posted on February 12th 2011 at 11:38 pm by Rich.

View more posts in Flash Game Dev Tips. Follow responses via the RSS 2.0 feed.

Make yourself heard

Hire Us

All about Photon Storm and our

HTML5 game development services

Recent Posts

OurGames

Filter our Content

- ActionScript3

- Art

- Cool Links

- Demoscene

- Flash Game Dev Tips

- Game Development

- Gaming

- Geek Shopping

- HTML5

- In the Media

- Phaser

- Phaser 3

- Projects

Brain Food