Game Development Category

-

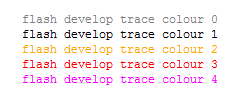

Colour your trace output with FlashDevelop

5th Jan 20115 This one surfaced on twitter today, and I thought it was so useful I’m blogging about it – for my own records as well as for the benefit of anyone else reading this.

This one surfaced on twitter today, and I thought it was so useful I’m blogging about it – for my own records as well as for the benefit of anyone else reading this.When using FlashDevelop (and if on Windows, there’s really no reason to use anything else) you can colour the output of trace statements in the Results manager by using the following syntax:

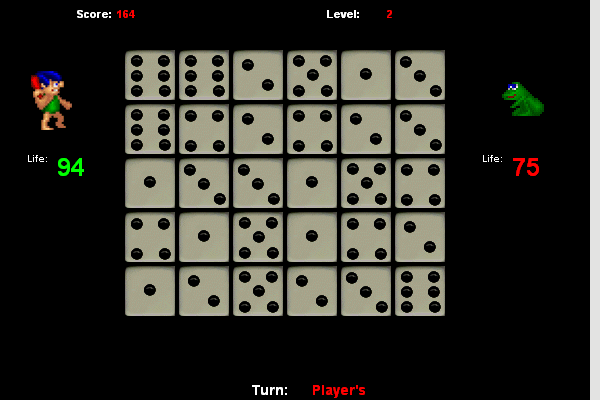

trace("0:flash develop trace colour 0"); trace("1:flash develop trace colour 1"); trace("2:flash develop trace colour 2"); trace("3:flash develop trace colour 3"); trace("4:flash develop trace colour 4");and it’ll look like this:

Obviously the important part is the number followed by the colon at the start of the trace.

Note that the above colours may be based on your FD colour settings. But it’s still superbly useful 🙂

-

Getting Your Flash Game Sponsored – Book Review

1st Nov 2010 Ryan Wolniak, fellow Flash game dev and owner of the popular freelanceflashgames.com was kind enough to send me a copy of his new book: Getting Your Flash Game Sponsored. This is a self-published title available to buy from his site for $20 in PDF form, or $30 as a paperback.

Ryan Wolniak, fellow Flash game dev and owner of the popular freelanceflashgames.com was kind enough to send me a copy of his new book: Getting Your Flash Game Sponsored. This is a self-published title available to buy from his site for $20 in PDF form, or $30 as a paperback.I felt it only fair that I should give the book a detailed but balanced review. So after reading it all that is what I present here …

The contents of this book start with “What is Sponsorship?” and cover a decent range of subjects from uploading to FGL, making your game “appealing”, dealing with the bidding process through to sale. There are over 160 pages of content, although depending on your experience as a developer some of them could be seen as filler.

It kicks off with the most important aspect of all – the variety of sponsorship offers out there, and the terminology that goes with it. Exclusive, Primary, Site-locked, Performance Bonuses, etc. It does a good job of giving the basics for each type although I did smile at the comment that “site-lock” sales usually are not “that much work” because you just switch out branding and drop in a new API. I’m sure I am not alone when I say that I’ve seen some portal APIs that would make you truly weep! And you should never under-estimate how long some API work can take. It’s not uncommon for the more complex ones to be a good evenings work (3+ hours). On the flip-side I do find that the most complex APIs come from the portals who pay the most.

I like the fact that Ryan mentions the selling of Source Code, although I didn’t agree with the statement that “You lose all rights to your game”. That is entirely specific to the deal you are making. I’ve sold the source code to a couple of my games, and both times they bought the rights to re-brand it for a single-use game and nothing more. It was an easy way to make a decent amount of money, although I know a number of developers who wouldn’t part with their code for all the tea in China.

There are some interesting stats in the Game Details section. Here we are told about the importance of naming our game well. The stats show how many words are optimal in your game title across both Kongregate and Newgrounds. The only issue I had was that the pie chart segments were all in very similar shades of blue making them hard to read. As you can imagine most games have between 1-3 words in their title. This chapter continues to explain the right way to handle thumbnails, game screen shots, your game description and then dives out into an 11 page tangent on video capture and production (should you wish to make your own game trailer). I honestly feel it would have been better to insert good examples of thumb nails, screen shots and really captivating game descriptions instead.

The Upload Process is essentially a guide to using the Flash Game License web site. There’s nothing wrong with this section, and it could be of help to newbies or younger developers. But I can’t help shake the feeling that if you’ve got to the point of being capable of coding your own game, then you’re almost certainly capable of filling out an upload form. Having said that it does help steer you through the jargon minefield you’ll encounter on the way.

The next chapter is on the importance of getting Feedback on your game. Again this is mostly about how to achieve this via FGL and using their First Impressions service. Both things I’d suggest you do. Although First Impressions are very hit and miss, they nearly always carry a core element of truth to them. Once you’ve collected your feedback it makes sense to improve your game based upon it, and there’s a chapter dedicated to doing exactly that. This walks you through improving everything from your main menu, to your instructions process (how you educate the player), to audio, highscores, upgrades and achievements. This is a big section. And for the most part it’s a really good one, especially for new developers.

On page 121 we hit the “Start the Bidding” process. Arguably the most important part of the book. It contains a lot of information direct from the guys who run Flash Game License, by way of lots of quotes about how their process works. This is useful stuff, and gives you a little insight into what’s going on behind the web site itself. There’s a huge section on dealing with emailing sponsors, how to talk to them, negotiation and managing your relationship.

I very much liked the fact that Ryan makes it clear that sponsors are “just people too” as this is bang-on. But I wish he’d expanded this section a bit to include “How to deal with asshole sponsors”. If you are being offered a duff deal, don’t take it. Walk away. If a sponsor is offering you grief via a horrendous API, or taking ages to process a payment, don’t be scared of making this known to them. While I agree that you should remain professional, you should never be made to feel intimidated. I once had a sponsor successfully win the bid on one of my games, only to email me a few days later saying “We’ve realised there is only one level in the game. Can you add some more?” – I was extremely annoyed because it clearly said the game had one level (that was actually the whole point of the game), and more importantly they were requesting something well beyond the price they’d paid for it. So I said “no”. All I can say is don’t let them take the piss – if a sponsor starts asking for changes to your game, or offering creative advice, don’t be scared of reminding them they aren’t the game designer – you are – and they sponsored the game in the state it was shown on FGL, and additional work will be charged for.

There’s a really nice Case Study from Bezerk Studios. Certainly one of the most successful Flash game development team working at the moment, it was really interesting to read about how they are constantly pitting bidders against each other. They demonstrate clearly that even after you’ve done everything this book recommends, and have tweaked your game to perfection, the best deals come down to constant negotiating and haggling, and that in itself is a fine art.

I’m in a mixed mind over the book. Ryan has done a sterling amount of work, collecting together helpful quotes and opinions from developers and sponsors alike. He’s covered all of the core areas of game sponsorship, if a little briefly in some places, and it’s written in a good conversational tone without making too many outlandish claims. However if you’ve already sold a game on FGL then there is probably very little you will read that hasn’t occurred to you already. If you are extremely new to the process, then it covers some solid ground in a decent amount of depth. At the end of the day only you will know if the book is worth your time or not, and there is always the “30 day money back guarantee” on the PDF version, which is a rare and brave thing to offer. I feel there are several sections that could have been added to this book, and some which it wouldn’t hurt from dropping. But as a self-published first attempt I can’t fault the enthusiasm on display here.

Getting Your Flash Game Sponsored is available from http://freelanceflashgames.com/getting-your-flash-game-sponsored/ (and yes I know the layout and copy on this page reads like one of those “Get Rich Quick” schemes – “I learned from their mistakes so you don’t have to!” (ick) but thankfully the copy of the book itself is far more approachable! So don’t let it put you off)

-

DAME – Great new map editor for Flixel

20th Sep 2010I’m a big fan of Flixel. Sure, it has its idiosyncrasies. But for rapid game development, or certain styles of game (fast paced pixel pushers) it’s perfect. One of its powerful features is the native tile map support. To create a tile map you can either bang one together in Notepad (if you’re pretty insane) or use a mapping tool. Some of the more popular ones are Mappy and Tiled, but neither were created for Flixel, or even Flash, and their feature sets are sadly quite lacking.

Enter DAME. Created by Charles Goatley this neat AIR app allows you to build complex 2D tile maps quickly and easily. As it uses Flixel for its rendering engine you know that whatever it looks like in Dame, it’ll look the same in your game too. I’ve been using it for several weeks now, during which time the developer has actively listened to feedback on the Flixel forum, and fixed bugs and added powerful new features.

You can put down multiple map layers, each with custom scrollfactor values and varying block sizes. Onion skinning, resequencing and editing is easy. One of it’s most powerful features is the handy matrix tool. By defining a grid of tiles you can then “paint” intelligently using this grid, and it’ll map all of the sides together sensibly. This allows for very rapid level generation indeed. With the new 1.0.5 update you can even assign custom tile connections, meaning you can set interior tiles as well. Hard to explain, but super easy to use, and once you have experimented you’ll be in tile mapping heaven.

Sprite layers are another great feature. Sprites can be imported and all of their Flixel attributes set, as well as any custom properties you may need. Sprites can be positioned anywhere, not just on the tilemap grid of the current layer, and can be rotated, scaled, flipped and duplicated. They can also be set to follow paths, which you can drag out and draw easily using polygons and splines. So if you had a platform sprite that you wanted to make follow a certain movement pattern, just draw it as a path and then attach the platform to it.

Text can also be added to the map (again any place, size or orientation). And shapes – both circles and boxes – can act as “triggers”. So you are able to draw a shape over an area of your map and have it trigger an event when the player enters it for example.

There are several exporters included (a complex and a simple one), and you can easily just export the map data as CSV if you wish to use Dame in a non-Flixel game. In fact you can even use Lua to script your own export system!

Dame is still very new and as such has a few teething troubles. But I would still encourage you to check it out and participate. The developer is friendly, responsive and open to ideas – lots of which I’ve seen implemented extremely rapidly. All quality attributes in my book.

-

The Essential Guide to Flash Games: Book Review

6th Sep 2010 Update: For a 25% off Discount code read to the end!

Update: For a 25% off Discount code read to the end!For the sake of transparency I just want to state: Friends of Ed offered me a free copy of this book for the purpose of reviewing it. However I declined as I had already pre-ordered my copy from Amazon, as I’m a great fan and friends with the authors Jeff and Steve Fulton. That doesn’t mean I’m going to treat this book with kid gloves or sugar coat my review however.

Dissecting a mammoth

Jeff and Steve Fulton, the pair responsible for the ever popular 8-bit Rocket web site, home to many tutorials on Flash game development, decided to combine their collective knowledge into one single tome. And this is the end result.

The book is split over 12 chapters which make up the majority of its 630+ pages. The chapters are split into two parts: Basic Game Framework and Building Games. It kicks off by going through their “Second Game Theory” which basically says your first game will always be utter tripe, and things only really start getting interesting from your second game and onwards (or if you are like me, your 10th game onwards). But it does cover some basic concepts such as proper object-orientated coding, but always in a game context. That is what I like most about this book, every snippet of information relates to making games, not some random computer science terminology you’ll never care about or commit to memory.

It then dives head first into building a game framework, including a solid and re-usable state machine, game timer and event model. By page 15 you have finished coding your first game, and while it’s a simple click counter it all runs from a well defined framework that is re-used and expanded upon throughout the rest of the book.

The second game is “Balloon Saw” in which you control a spinning blade with the mouse, and must take out as many floating balloons as possible. Again it’s simple, but it introduced more important new concepts: level progression, player controls, collision detection and scoring. By page 30 it’s all over, the lessons are learnt, you’ve another game under your belt and they waste no time in jumping into the 3rd game: Pixel Shooter.

Once Pixel Shooter is over you’ve got a complete space invaders style game finished, and more importantly they don’t dwell on every aspect of it – but only those aspects that differ from the previous game. I’m a big fan of learning through iterations, and that is certainly how this book approaches things.

Once you hit Chapter 2 it’s all about strengthening the framework you’ve already put in place. They add lots of powerful new features such as Custom Events handlers, a Basic Screen handler, Buttons and a Score Board (which is more the in-game UI for scores, not a Mochi Leaderboard type affair). Several pages are dedicated to the package structure, creating the game stub (which is done via FlashDevelop) and just setting your project up in a nice and clean way. Again I’m a big fan of this approach, and I have my own “template” project structure that I roll-out for all new games I write which matches theirs very closely. You don’t have to follow their structure to the letter (although it would be useful if following all of their game builds in the book), but by all means take from it the parts you find most useful, and settle on what works best for you. But the final message is the same: don’t be messy.

By page 100 the framework is in place. This is quite a hard-going chapter, and while vital for the rest of the book I can see a lot of developers getting that glazed look in their eye as they pour through page after page of class set-up and variable declarations. As important as it is I can’t help but feel that it may have been better to keep up the earlier frenetic pace of game building, and drip-fed more of the framework in the same manner.

Once the framework is in place Chapter 3 creates the “Super Click” game, an iteration of the very first game made in the book. It starts off by getting the reader to create a really brief game design document. All it asks you to do is write a very short snippet about what the game is, and define the basics such as the name, the objective, a description of play and creating a list of required assets/logic/variables.

It may seem long-winded to be doing this for such a simple game, most of which you argue you could just “remember” rather than write down. But GDDs are a tried and tested practise found in the industry. Any game developer I have working in my team will all have to write GDDs before they touch a line of code, and Jeff and Steve are the same. So if you plan on making Flash games as a “pro”, don’t skip this part.

Taking some Flak

As you may expect by now Chapter 4 is all about creating yet another game. This time a homage to Missile Command only with boats and planes. Jeff and Steve are children of the 80s and the Atari blood runs deep through their veins. You’ll see this scattered through-out the book, not least of which is a whole page dedicated to the history of Missile Command and it’s variants opening this chapter! As a fellow Atari fan I loved these sections, but I can see why the younger developers reading the book may care a lot less.

Flak Cannon, and indeed all remaining games in the book, use sprites from Ari Feldman’s now infamous SpriteLib collection. It also gets all sound effects from the SFXR app. So sadly it’s going to look and sound quite dated before it’s even left the gate. Now I’m a massive retro gaming fan, and I have utmost respect for the “classics” and reinventing them in Flash. But even I don’t feel that SpriteLib is a strong enough graphical resource for a book like this. Jeff and Steve would have benefited massively from employing the talents of a real pixel artist, who could have created something beautiful for each of the games in the book. I don’t think that visually any of the games portray just how solid and robust a framework is powering them. My concern is that developers will take one look at the games on offer and visually dismiss them, asking why they look so “old”. This is a crying shame, as internally they are as fresh as can be, employing all of the modern tricks and techniques you need for a flash game these days. It’s just the surface gloss that doesn’t match.

Work your way through the Flak Cannon game build and at the end you’ll have a really powerful Sound Manager class added to your arsenal, along with an understanding of vector movement and angles in Flash. This is where my second biggest criticism of the book stems: there are many absolute nuggets of code gold buried in the 630 pages of this book, but they require some serious digging to extract. Although the index and contents do a good job of explaining when you’re about to learn a new technique, such as Line of Sight, AI or 2D Cameras, being able to extract those techniques out from the game in which you’re learning them is not an easy task. There’s very little “throw this code into the IDE and see”. For example the minimax-styled AI routine used in the game Dice Battle is so tightly ingrained into both their framework, and the game itself, that you’d have a harder than necessary time extracting it for your own project.

It’s all about post-retro, baby!

The love of all things bitmap starts with the Flak Cannon game, and really doesn’t let-up from there on. By the time you hit Chapter 6 (“No Tanks!”) you’re well down the road of tile editors, Mappy, sprite sheets and blitting. There is no denying that this is the fastest way to shift graphics around in Flash, but it’s not the only way. And it may feel very alien for devs coming direct from the Flash IDE to even bother with the likes of a sprite sheet and non-timelined animations. The tilemap system introduced in chapter 10 is again all about the blit and “old-school” tilesheets.

Personally I don’t have a problem with this, but I think it’s important for devs to realise that when coming to this book that is the approach they are going to be taken down. And while it’s a tried, tested and very fast route to pursue, it’s also not the only one. There were many times reading this book that I felt it should have been called “The Essential Guide to Building Bitmap Blitted Games in Flash”, because quite frankly there is no other book that covers this subject in the kind of depth the Fulton’s do. And I doubt there ever will be (unless they publish a 2nd edition!)

Towards the end of the book Chapter 12 deals with a host of important topics that you rarely see mentioned in any other Flash game book. They cover making money from your game, via both Mochi Ads and licenses / sponsorships. Securing your game with site locking and encryption, marketing, pre-loaders and Mochi leader boards. I thought this was a really nice touch, it just makes it all seem more “real” – as these are all the kinds of things that new Flash game devs will go through, and may not yet be aware of.

Game Over Man, Game Over

I truly admire Jeff and Steve for having had the balls to even write this book in the first place. I know just how much hard work it was, and how much effort they put into it. Does this cloud my judgement somewhat? Perhaps, but ultimately it’s up to you to decide if this book will be a “good fit” or not. Personally I’m a firm believer that you can never have too many game development books, and this is one that certainly has a place on my bookshelf. There are quite a few typos and spelling mistakes to be found (“MoveClip” being a popular one!), and even their game Super Click says “Click the blur circles” at the start (it should be “blue”). But I can overlook these small things. Hopefully they don’t extended into the source code too!

Yes it’s very “hardcore” about the approach (blit-mapped to the max), but only because they care about performance. They cover a lot of advanced game making topics, and a lot of subjects that no other book even looks at. They teach you and they teach you rapidly, pulling no punches, and without much filler.

If you’re the sort of developer who just “dips into” books, and extracts only the bits you need at that point in time, then you’re going to have to work a lot harder with this title. The content is there, but mining and then refining it into a usable state will take longer than perhaps should be necessary.

If however you have the tenacity to work through this book from start to finish, then I have no hesitation that you’ll come out the other end knowing a great deal about game development in Flash. You’ll have a whole ammo case full of fantastic routines to use, all sitting on-top of a solid and easily expanded framework. And to me that’s worth the cover price alone.

Buy the paper version from Amazon

Special Offer: Buy the PDF eBook version and get 25% off by using the code PHOTONSTORMECN

-

10 things I took away from The Children’s Media Conference

6th Jul 2010

Last week I attended the Children’s Media Conference with lots of other people from Aardman. It was a 3 day mix of presentations, panels and meeting really interesting people. And everyone there had something to do with the children’s side of the media and entertainment industry. I just wanted to share a few insights that I picked up there. Some are obvious, some less so …

1.) Children are no longer just watching TV, they expect to interact with it. On their phones, via MSN, on YouTube, etc. And often do these things simultaneously (watching a show while chatting to friends about it). The distinction between TV and online is a non-plus for them. They have an extremely rich media diet.

2.) Traditional broadcasters (and “offline” producers) are increasingly worried they are taking too long to resolve the provision of content. And children are just going online instead. The world is changing faster than a lot of them can cope with.

3.) Children prefer “home grown” material – i.e. they don’t want to hear American voices in their cartoons. The same applies to games, only to a much lesser extent.

4.) Broadcasters recognise that the future is on-demand, and in the long term, online. The BBC specifically made a point that they were perfectly aware that digital is the future.

5.) Lots of Children love manga! (no surprise there) The style of artwork allows them to clearly see the emotions that the characters are experiencing. And manga / anime characters do actually show emotion, unlike most US made cartoons in the same area. They find the super powers and stories generally more exciting, and want to be part of that fantasy. There is a really strong “collect, compete, play” association with most popular manga/anime (think Pokemon, Yui Gi Oh or Bakugan). Manga/Anime is less concerned about dealing with emotion and more complex subjects.

6.) “Transmedia” is now what they are calling the latest iteration of “new media”. But it’s all just media really. Transmedia (like before it) is just the means of telling or experiencing a story across multiple platforms.

7.) “Games Bibles” are vital, no matter what scale game you are working on. Matt Costello gave a brilliant (although sadly very brief) talk about how he created the game bibles for games like Doom 3 and Just Cause 2. They should start off as a paragraph, explaining the concept behind the world in which the game lives. And then expand from there, eventually encompassing as much detail as possible in order to bring the game alive. Bibles shouldn’t just focus on the game itself, but look into the backstory and what could happen in the future, should the series run or adapt across to a different media (game made into a TV show or comic for example).

8.) Girl Gamers: Girls love tech! They adopt it way ahead of boys. By 8 years old most of them will own a gaming device (like a DS), by 10 lots will have a mobile phone of their own and a laptop/PC. By 11 they’ll have Facebook accounts (and boys will have XBLA accounts). By 13 most have personal iTunes accounts or equivalent. Between the ages of 9-10 is when most girls peak at their interest of gaming. They are competently using online services (for social and gaming aspects) and use of their mobile is massive. Age 10+ and they mostly now focus on social spaces and social networking. To them Facebook IS a game. Creating private worlds is key, the ability to build a social space away from their home.

9) Games that can tick the following subject boxes appeal strongly to girls aged 10-13: Manipulation (!), Relationships (Sims), Problem Solving (puzzles), Responsibility (pet games), Private Worlds, Role Playing (Imagine Teacher), Identity, Risk Taking. In reality most games fail to keep their long-term interest. A quote from a 10 year old: “I classify my phone and my laptop as my toys”. The Blackberry mobile phone is huge for girls and is often their top “most desired” item. This is due to the social nature / features it provides (Blackberry messenger). Social networking for them becomes obsessive around age 12. By age 13 they want cues from the real world in their games.

10) Graphic Novels and Comics are making a huge come-back for children, and are no longer mostly for adults! Publishers like Walker Books are reporting sales up by 29% over the previous year. They are finally coming “back to kids” – picture books aimed at 8-9 year olds (such as Savage by David Almond) are breaking new ground. Visual literacy is just as important as reading ability. Jamie Smart gave a brilliant talk about how he can release a new comic strip on his web site, and earn a decent living from the merchandise surrounding it. The team at Pulp Theatre are releasing graphic novels through their Alien Ink range, aimed at teenagers and issues they find hard to talk about. Has been a huge success, now sponsored by Channel 4. Again they did the whole range of releasing online and on Facebook before going into print form. They took the comics to where the kids hang out, they didn’t expect them to “come find them”.

Please bear in mind that figures given should be taken in the context in which they were delivered (i.e. are probably only relevant to the UK)

Despite the heat wave it was a great conference. And interesting to see how other people are applying the same kinds of professional skills that we have (from web development to game design) and applying those to entertaining and educating children. Perhaps even yours? 🙂

Hire Us

All about Photon Storm and our

HTML5 game development services

Recent Posts

OurGames

Filter our Content

- ActionScript3

- Art

- Cool Links

- Demoscene

- Flash Game Dev Tips

- Game Development

- Gaming

- Geek Shopping

- HTML5

- In the Media

- Phaser

- Phaser 3

- Projects

Brain Food